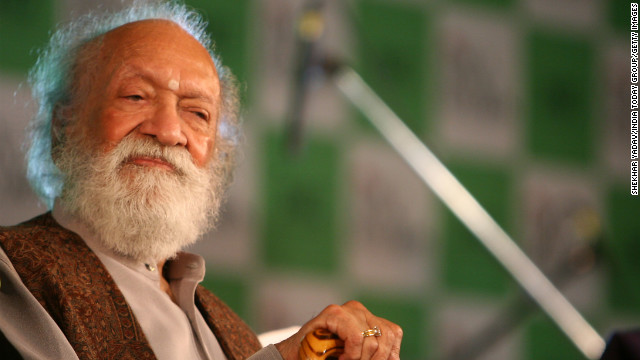

Pandit Ravi Shankar died Tuesday,

December 11, at age 92. The legendary sitar player brought Indian music

to the West and taught Beatle George Harrison how to play the

instrument.

Pandit Ravi Shankar died Tuesday,

December 11, at age 92. The legendary sitar player brought Indian music

to the West and taught Beatle George Harrison how to play the

instrument.

HIDE CAPTION

Sitar legend Ravi Shankar

- Ravi Shankar transcended difficult boundaries between East and West

- He had a way of making the complexities of Indian classical music accessible to people

- The writer recalls the first time she heard him play

- He was a name Indians uttered when they wanted to boast of their homeland

Panditji, as he was known to his fans, did it by remaining true to his craft.

"He was an amazingly pure artist," says Kartik Seshadri, one of Shankar's pupils and a sitar master in his own right.

Though he's often thought

of in the West as an experimenter and collaborator -- with guitarist

George Harrison, violinist Yehudi Menuhin, saxophonist John Coltrane,

composer Phillip Glass and conductor Andre Previn -- Shankar was a

traditionalist.

Indian classical music,

as ancient as the scriptures of Hinduism, flowed from his fingers with

ease. His music transfixed even those who knew not one iota about the

complexities of it.

"That is the beauty of

his approach to music and how he was able to transfer that and translate

that to an audience in the West," Seshadri says.

Shankar's music moved from introspective to playful.

Remembering Ravi Shankar

Remembering Ravi Shankar

"There's a whole gamut of emotions that finds a place with people," Seshadri says.

Shankar died Tuesday in San Diego, his home for many years. He was 92 and led a life rich with accomplishments and accolades.

I was one of those people who was transfixed the first time I listened to Shankar.

I was still in high

school in Tallahassee, Florida, when Shankar and his troupe came to town

for a performance at Florida State University's music school in

December, 1978.

There were only a

handful of Indian families in Tallahassee then, and not much was

available to us in the way of homeland culture. It was a rare treat for

us to be able to see Shankar in concert.

My mother was especially

excited. She was trained in voice and sang the songs of another

talented Indian, Rabindranath Tagore, India's sole Nobel laureate in

literature. She played harmonium with her songs and sometimes, a

tanpura, a string instrument that resembles a sitar but has no frets.

It was a moment of

pride, as well -- in a time when India was known to many of my American

friends as a land of human misery. When we wanted to boast of the

greatness of our land, we uttered Shankar's name.

A few days before the

concert, organizers called my mother with a special request: Could she

possibly cook dinner for the musicians? Shankar was craving a

home-cooked Bengali meal.

Of course, yes, my

mother said. Who would not be honored to cook for the maestro?

Then came days of cooking -- spiced rice pilau with raisins and

pistachios, chicken curry, lentils and sandesh, a special milk sweet for

which Bengalis are famous.

On the night of the

performance, Opperman Music Hall was packed. The lights dimmed and the

Shankar's music filled the air, mellifluous and luscious like the rich

silk of a Benarasi sari.

I didn't understand the melodic forms and rhythms of the music that was played that night.

I knew that he had

written the music for director Satyajit Ray's acclaimed "Apu Trilogy."

But I was not unlike millions of others who connected Ravi Shankar's

name to the Beatles and to the concert for Bangladesh.

I had expected to react

in typical teenage fashion with boredom. Instead, I was transported to

another sphere. Shankar's sitar was magical.

His music transcends the boundaries of race and religion. It is what humanity is all about.

Journalist Partha Banerjee

Journalist Partha Banerjee

The rhythms of the

performance fell and rose with the improvisation of each melody

framework known as a raga. His sitar told of joy and sorrow, of lives

led and dreams dashed.

The intensity on stage rose as Shankar challenged tabla virtuoso Alla Rakha to match each one of his sitar riffs.

I did not just hear a performance that night. I felt it.

Later that evening Shankar and Rakha arrived at our house. I sat in awe through every course of my mother's dinner.

It was my introduction

to the classical music of my homeland. I realized then that I didn't

need to understand the nuances of the notes. Shankar spoke to me in a

language that was universal.

"He created an aura of spirituality," says journalist and musician Partha Banerjee.

"His music transcends

the boundaries of race and religion. It is what humanity is all about."

Harrison dubbed Shankar the "godfather of world music." Many Indians

like to think of him as their cultural ambassador to the world.

Had he been born a Westerner, he might have been a household name like Beethoven or Mozart, Banerjee believes.

In later years, Shankar

said he was happy to have contributed to bringing the music of India to

the West, though he regretted his name forever linked to a 1960s culture

of drugs, sex and rock 'n' roll. The music he played, he said, was

sacred.

Hallowed, even.

Not many ordinary Indians I know would eject their Bollywood CDs to listen to Shankar's sitar. He's not on top-40 lists.

But Ravi Shankar's gift

went beyond his skills on the strings. He possessed an uncommon ability

to reach across cultures. He introduced the traditions of my homeland to

my friends in America.

And he did it by touching their souls.

Source: edition.cnn.com

No comments:

Post a Comment